Dr. David Maberley is a retina specialist at The Ottawa Hospital. He provides medical and surgical care to patients referred to him for a range of retinal conditions, including AMD. For Dr. Maberley, the most rewarding part of treating patients with AMD is being able to offer them reassurance that, with therapy, vision can often be stabilized and, in some cases, improved.

What is AMD?

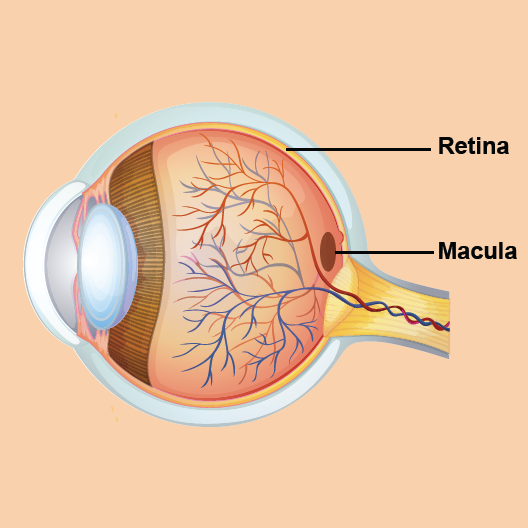

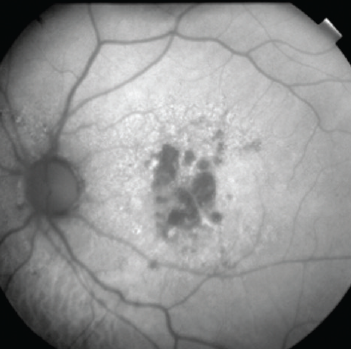

AMD is a condition that affects the retina and, specifically, the macula. The retina is a structure at the back of the eye made of light-sensitive tissue. It acts like the film in a camera; it converts light into a signal that the brain interprets as an image. At the centre of the retina is a small area called the macula that allows us to see fine details clearly. A layer of cells underneath the retina provides it with nutrition and allows it to function healthily. This layer of cells is called the retinal pigment epithelium.

AMD happens when cells of the macula begin to break down or deteriorate, causing loss of central vision. With AMD, one loses the sharp, detailed vision necessary for activities like driving, reading, and recognizing faces.

What’s the difference between wet and dry AMD?

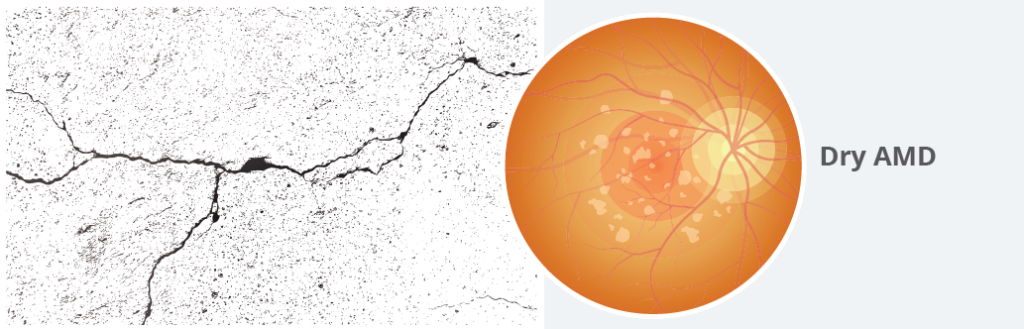

To understand the two types of AMD, you can think of the retina and underlying cells as a sidewalk. It starts off as a smooth, paved sidewalk, but over the course of many decades, the sidewalk starts to crack and crumble. This is like what happens with dry AMD. The cells of the retina start to deteriorate. Symptoms of vision loss occur gradually and slowly worsen over time.

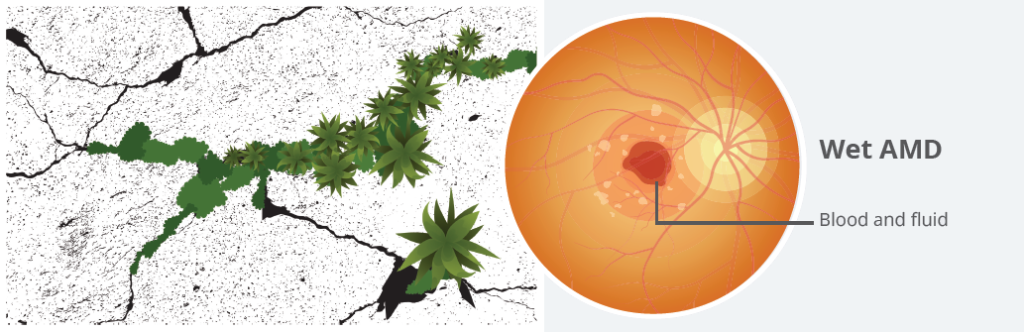

Sometimes, small trees start to grow through the cracks in a sidewalk. These can push apart the edges of the sidewalk and cause a lot of damage in a short amount of time. This is what happens to the eye with wet AMD. Blood vessels can start to grow up through weakened areas under the outer retina. These vessels bleed and leak fluid, causing swelling and scarring, which lead to vision loss. Because damage happens relatively quickly, wet AMD has a more sudden onset of vision loss compared to dry AMD.

I’m a woman in my late 50s. How can I lower my risk of developing AMD?

It’s great that you’re being proactive about your eye health. When it comes to AMD, however, the strongest risk factors are largely out of our control. The biggest risk factor is age; we typically see AMD starting to develop in those over 70 years of age. We also now know that about 80% of AMD is driven by genetic predisposition.

You may also be at a higher risk of developing AMD if you:

- Smoke

- Eat a diet high in saturated fat

- Have chronic conditions like obesity or hypertension

Quitting smoking, eating a healthy diet (including foods rich in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids), getting regular exercise, and keeping other health conditions in check may help lower your risk of AMD.

While you can’t control all risk factors, the best way to protect your vision from AMD is to get regular, comprehensive eye exams so that AMD can be detected and treated early.

Ophthalmologist Dr. Setareh Ziai shares more lifestyle tips for keeping our eyes healthy

My optometrist noticed some changes in my retina. I’ve been referred to an ophthalmologist to confirm if I have AMD. What can I expect from my upcoming appointment?

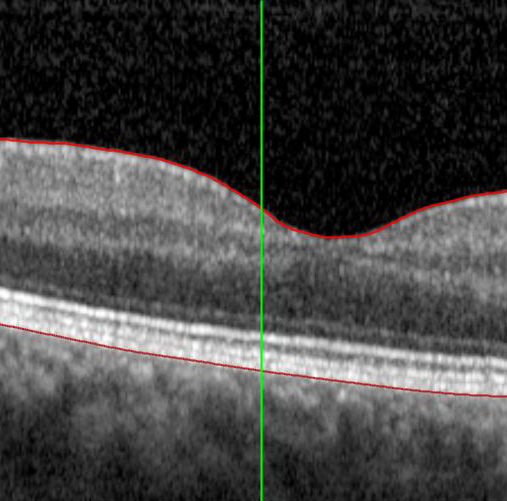

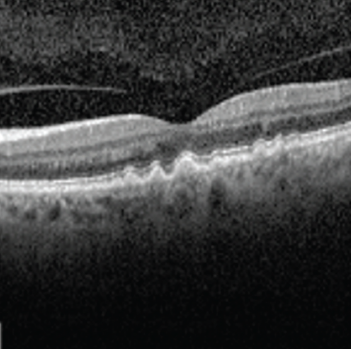

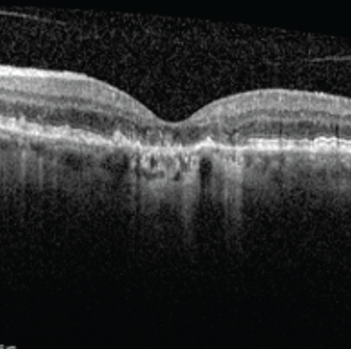

Your referral to an ophthalmologist will allow you to get a definitive diagnosis of AMD (or rule out other conditions that may be affecting your retina). Typical assessments for AMD include a vision test and a full eye exam, including a retinal exam. You’ll likely also have an imaging test done called optical coherence tomography (OCT). This is a non-invasive laser scan of the back of the eye. It allows your ophthalmologist to see areas of the retina that may be damaged or dying and whether there are any abnormal blood vessels. Based on what your ophthalmologist finds with these tests, further imaging might be needed.

Once a diagnosis is made, your ophthalmologist will be able to provide treatment recommendations and, if appropriate, start therapy. Depending on where you live and the complexity of your condition, you may also be referred to a retina specialist to manage your care.

How do AMD treatments work to prevent vision loss?

In wet AMD, a protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) encourages abnormal blood vessels to grow under the macula. These blood vessels can leak and bleed, forming scar tissue under the retina, which causes permanent vision loss. The good news is that we have medications known as anti-VEGFs that target these abnormal blood vessels. Anti-VEGFs turn off blood vessel growth and leakage and cause the abnormal blood vessels to shrink and fade away, preventing further vision loss. As the fluid around these vessels dries up, symptoms of vision loss can even improve.

Unfortunately, there are no medical treatments available yet for dry AMD. A specific high-dose vitamin regimen known as AREDS 2 has traditionally been used for people with dry AMD. Evidence suggests it may slow disease progression. It has also been shown to reduce the risk of dry AMD progressing to wet AMD. If you have dry AMD, ask your ophthalmologist if you might benefit from the AREDS 2 supplement. Health Canada is currently reviewing an injection treatment that might slow the progression of geographic atrophy (advanced dry AMD). This is likely to be available in mid to late 2024.

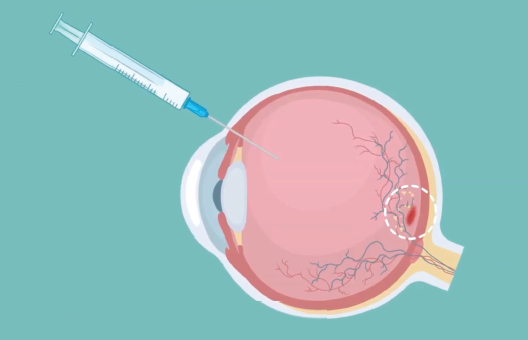

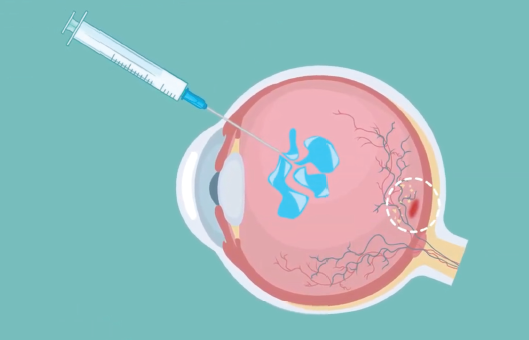

Anti-VEGF drugs are administered by intravitreal injection, which is a procedure used to place the medication directly into the space in the back of the eye called the vitreous cavity. The procedure will be performed by your ophthalmologist or retina specialist in their office, and the entire process only takes about 5-10 minutes.

Your ophthalmologist will numb your eye and eyelid with anesthetic eye drops or gel to reduce pain. Then the eye is cleaned to minimize the risk of infection. The anti-VEGF medication will be injected through the white part of the eye with a very small needle. You might feel some pressure or discomfort with the injection, and you might also feel a short sharp pain.

While there are few side effects from anti-VEGFs and complications are rare, there is always a small risk of infection. If you notice any worsening pain or redness that develops a couple of days after your injection, call your ophthalmologist’s office.

My mother mentioned that she has noticed some blurry vision. Is this just a normal part of aging?

I think it’s critical for everyone to understand that vision loss as we get older is not normal. If you have a sudden change or deterioration in your vision, there’s very likely an eye condition at play that may be treatable.

Since AMD is the leading cause of blindness in Canada, it’s important to be aware of the risk as you get older. All adults over the age of 65 should have a comprehensive eye exam at least every year so that any signs of AMD (or other serious eye diseases) can be detected early and treatment can be started before vision loss occurs. If you develop any visual symptoms, like blurred or distorted vision or patches of vision loss, don’t ignore them – seek attention immediately.

“Aging does not mean you have to lose vision. There’s so much out there we can offer to keep most people seeing throughout their lives.”

I’ve just been diagnosed with wet AMD. How long will I need treatments for?

Treatment for wet AMD requires a long-term commitment. In my discussions with my own patients with AMD, I always focus on the importance of consistent follow-up. Typically, after the first few monthly injections, anti-VEGF drugs are given less frequently and are often only needed every 2-3 months. We may shorten or extend the time between injections depending on how the patient is doing, but you’ll likely be in relatively intensive therapy with your ophthalmologist for a few years. Even when we’re able to get control over the macular degeneration and your injections are reduced or possibly even stopped, there’s always a risk of recurrence and a need for ongoing monitoring.

We don’t yet have treatments available that can reverse the damage caused by advanced wet or dry AMD. But for people who end up with permanent vision loss, it’s important for them to understand that we have tools we can offer them even if there’s nothing more that can be done therapeutically. Vision rehabilitation therapy is a rapidly evolving area of specialty care in ophthalmology that helps people function better with their remaining vision. Treatments might include magnification or training patients to use parts of their retina that are still functional. It provides patients with strategies and devices to maximize their remaining vision and improve their ability to manage in their daily lives. There’s a lot that can be done with technology like speech-to-text, text-to-speech, magnifiers, telescope glasses, and closed-circuit televisions to help individuals with vision loss lead more independent, active lives. If you have low vision due to AMD or another serious eye disease, talk to your ophthalmologist about getting a referral to a vision rehabilitation clinic.

It’s certainly an exciting time for AMD, with innovations on the horizon that will improve AMD care in Canada. For wet AMD, next-generation anti-VEGF drugs are in development that may be more durable than currently available options. These would mean patients wouldn’t need to receive injections as often. We’re also anticipating new treatments coming to market soon for geographic atrophy (GA) – a currently untreatable late-stage form of dry AMD. In GA, photoreceptors are completely lost, first in patches and then progressing throughout the macula. Clinical trials have shown promising results in slowing the progression of this form of dry AMD.

Other types of therapies are in early investigational stages. Gene therapy is being studied to help the eye produce its own anti-VEGF that would prevent the disease from worsening. You might also have heard some buzz about stem cell therapy as an opportunity to replace the damaged retinal cells. These cell transplants would potentially ‘repave the sidewalk’, if you will. The studies are still very early, so this treatment option isn’t on the near horizon just yet.

Other areas of advancement are in diagnostics and monitoring. Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) is an imaging technique that’s useful for more clearly defining the areas of damaged cells in dry AMD. The images can be coupled with AI algorithms to help track disease progression and monitor lesion growth. Once this machine learning technology is widely available at the clinic level, it will give us another tool to monitor advanced forms of AMD.

Inexpensive monitoring technologies that detect distorted vision are also being studied in clinical trials. These devices have the potential to be used in patients’ homes, with data relayed directly to their ophthalmologists so that follow-up plans can be adjusted accordingly.

With these and other promising advancements, the future of AMD management is looking bright.